Shifting Borders, Creating Polygons from Lines

Source:vignettes/shifting_borders.Rmd

shifting_borders.RmdOne of the most tedious tasks regarding spatial RDDs is the execution

of so-called placebo checks. With these, one has to show that the

postulated effect disappears when the RD cutoff is shifted around. In

other words, the regression coefficient on the treatment indicator has

to be statistically insignificant when the RD estimation is carried out

on any additional border. Just shifting around the border would be

already very cumbersome when it is carried out in a “point and click

fashtion” in a GIS API such as QGIS or ArcGIS. Here in R, thanks to the

sf package and its simple features, this is not that much

of a problem as we saw in the main vignette of SpatialRDD

already1.

The more tedious task, however, is that we need to determine which dots

on the map are the newly (placebo-)treated ones - after we moved our

cutoff. Simple distance calculations to the border do not help because

they don’t tell us on which side of the cutoff a point is. Since borders

are never straight lines and always have odd shapes, we also cannot just

come up with a rule based on x- and y-coordinates. And even if we could

it would be very tedious to figure out after every shift which were the

exact positions in space below/above the units count as treated. Thus

the only generalizeable solution left is to come up with a polygon

vector that covers the placebo-treated area. This vector can then be

used to do a spatial intersect and assign placebo-treatment and

placebo-control for every shifted border. That’s where the

SpatialRDD package comes in with a very generic solution

that allows the user to carry out a myriad of such placebo checks

without having to worry much about details.

library(SpatialRDD); data(cut_off, polygon_full, polygon_treated)

library(tmap)

set.seed(1088) # set a seed to make the results replicable

points_samp.sf <- sf::st_sample(polygon_full, 1000)

points_samp.sf <- sf::st_sf(points_samp.sf) # make it an sf object bc st_sample only created the geometry list-column (sfc)

points_samp.sf$id <- 1:nrow(points_samp.sf) # add a unique ID to each observationMore on placebo bordering

When the border is not approximating a line in space but is curving

and bending (i.e. in most cases), “placebo bordering” can be tricky and

is not straightforward. The simple subtraction/addition of a specified

distance from the distance2cutoff variable is also not a

very accurate description of a placebo boundary. On top of that, with

such a simple transformation of the distance column we can at best do a

placebo check on the “pooled” polynomial specification as the border

segments change and thus the assignment of fixed effect categories. A

placebo GRD design with an iteration over the boundarypoints is

literally impossible in such a case.

For a proper robustness check we thus have to create a new cut-off from

which we then can extract the corresponding borderpoints (with

discretise_border()) and also assign the border segment

categories for fixed effects estimations (with

border_segment()).

The shift_border() function can execute three different

(affine) transformations at the same time:

-

"shift"in units of CRS along the x- & y-axis (provided with the optionshift = c(dist1, dist2)) -

"scale"in percent around the centroid, where0.9would mean 90% -

"rotate"in degrees around the centroid with the standard rotation matrix \[ rotation = \begin{bmatrix} \cos \theta & -\sin \theta \\ \sin \theta & \cos \theta \\ \end{bmatrix} \]

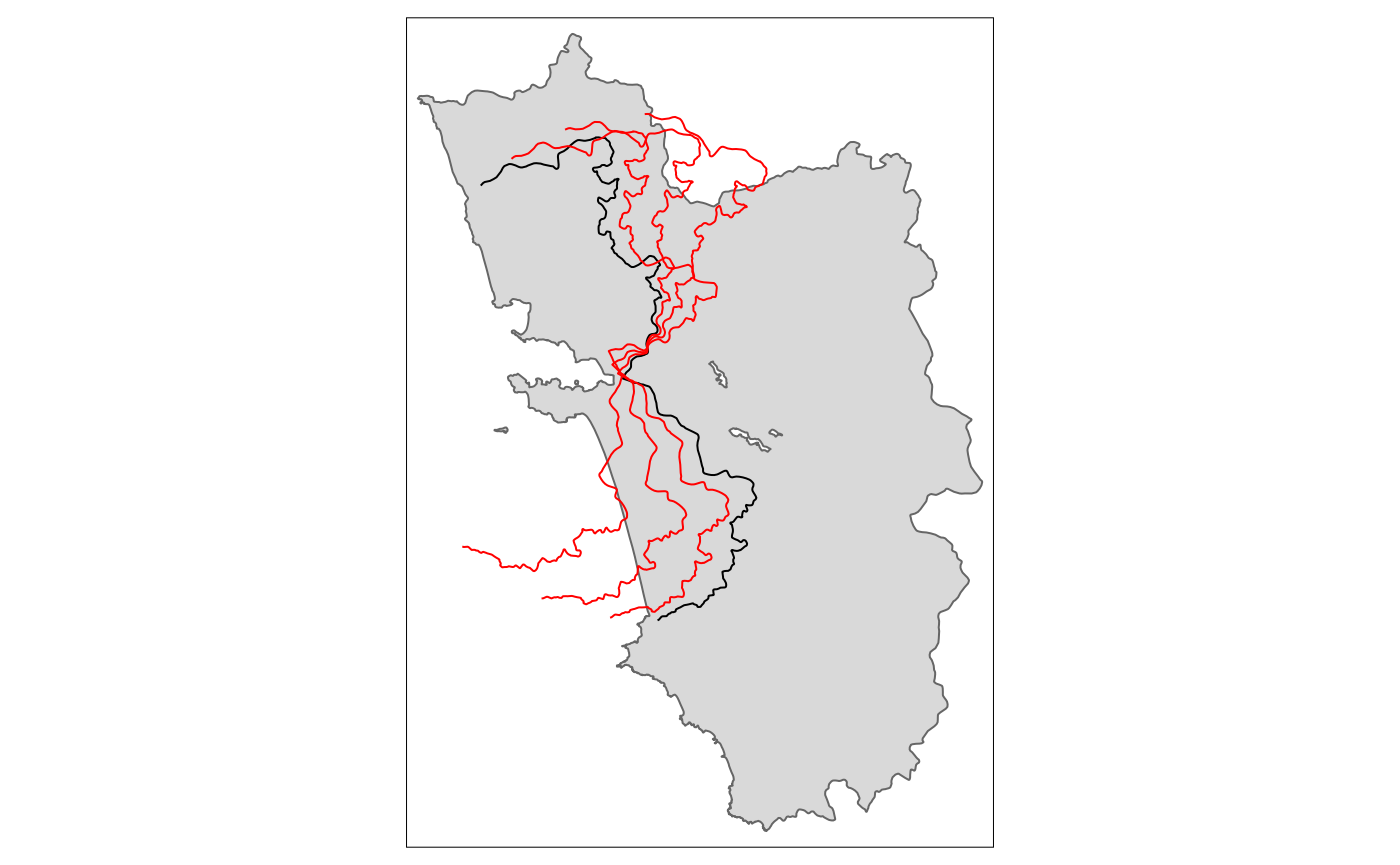

Rotate

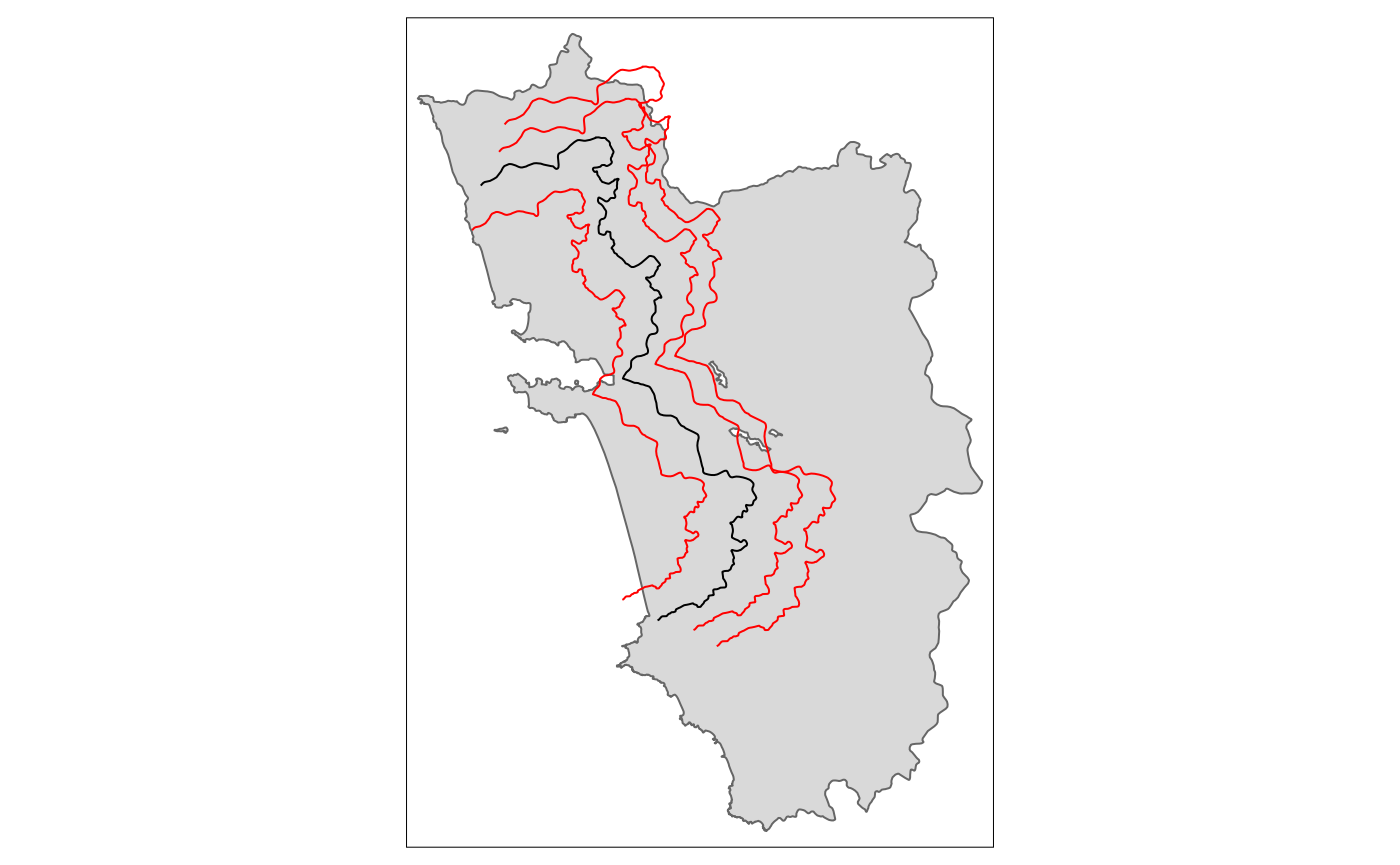

tm_rotate.sf10 <- shift_border(border = cut_off, operation = "rotate", angle = 10)

tm_rotate.sf25 <- shift_border(border = cut_off, operation = "rotate", angle = 25)

tm_rotate.sf45 <- shift_border(border = cut_off, operation = "rotate", angle = 45)

tm_shape(polygon_full) + tm_polygons() + tm_shape(cut_off) + tm_lines() +

tm_shape(tm_rotate.sf10) + tm_lines(col = "red") +

tm_shape(tm_rotate.sf25) + tm_lines(col = "red") +

tm_shape(tm_rotate.sf45) + tm_lines(col = "red")

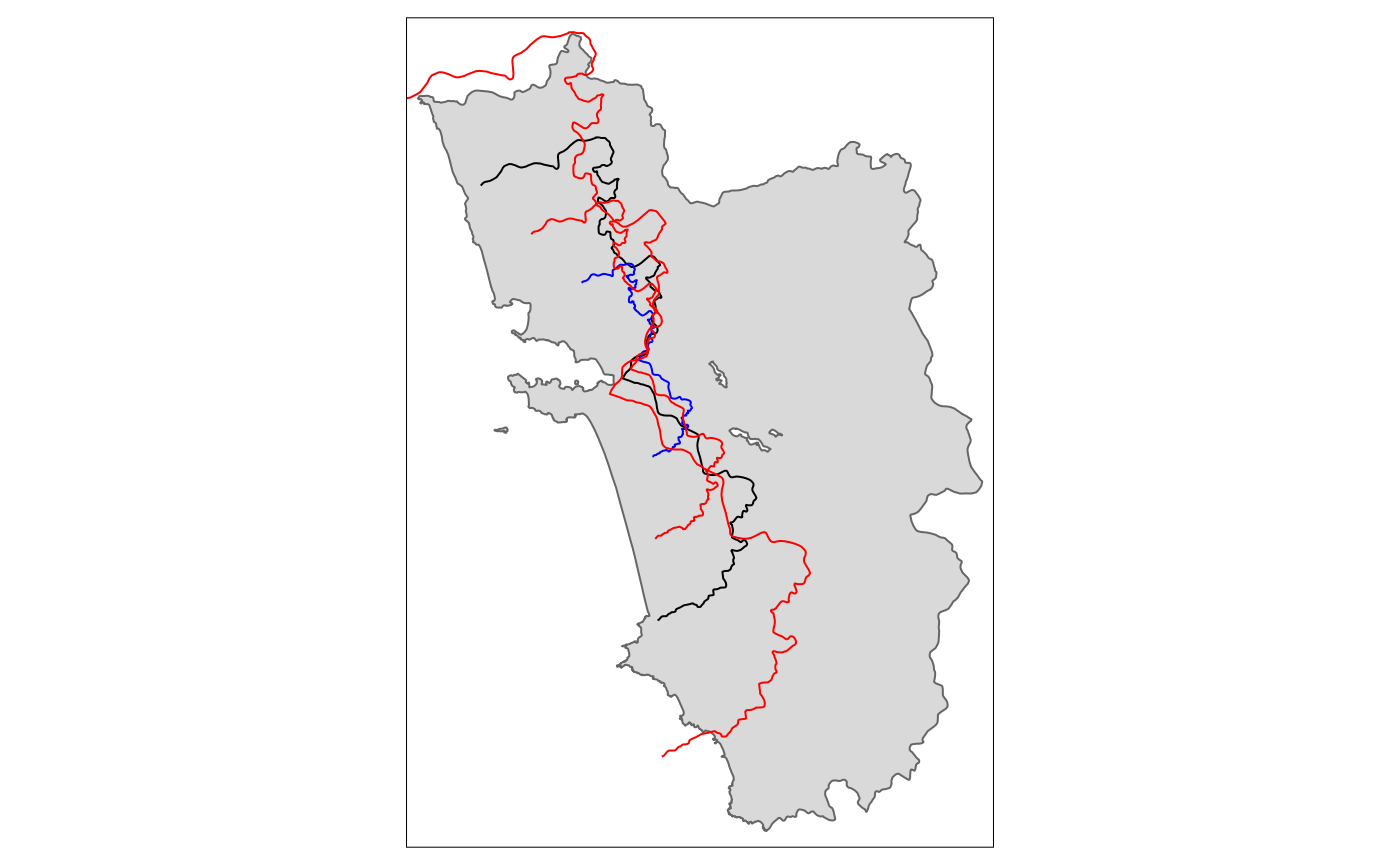

Scale

tm_scale.sf.4 <- shift_border(border = cut_off, operation = "scale", scale = .4)

tm_scale.sf.7 <- shift_border(border = cut_off, operation = "scale", scale = .7)

tm_scale.sf1.5 <- shift_border(border = cut_off, operation = "scale", scale = 1.5)

tm_shape(polygon_full) + tm_polygons() + tm_shape(cut_off) + tm_lines() +

tm_shape(tm_scale.sf.4) + tm_lines(col = "blue") +

tm_shape(tm_scale.sf.7) + tm_lines(col = "red") +

tm_shape(tm_scale.sf1.5) + tm_lines(col = "red")

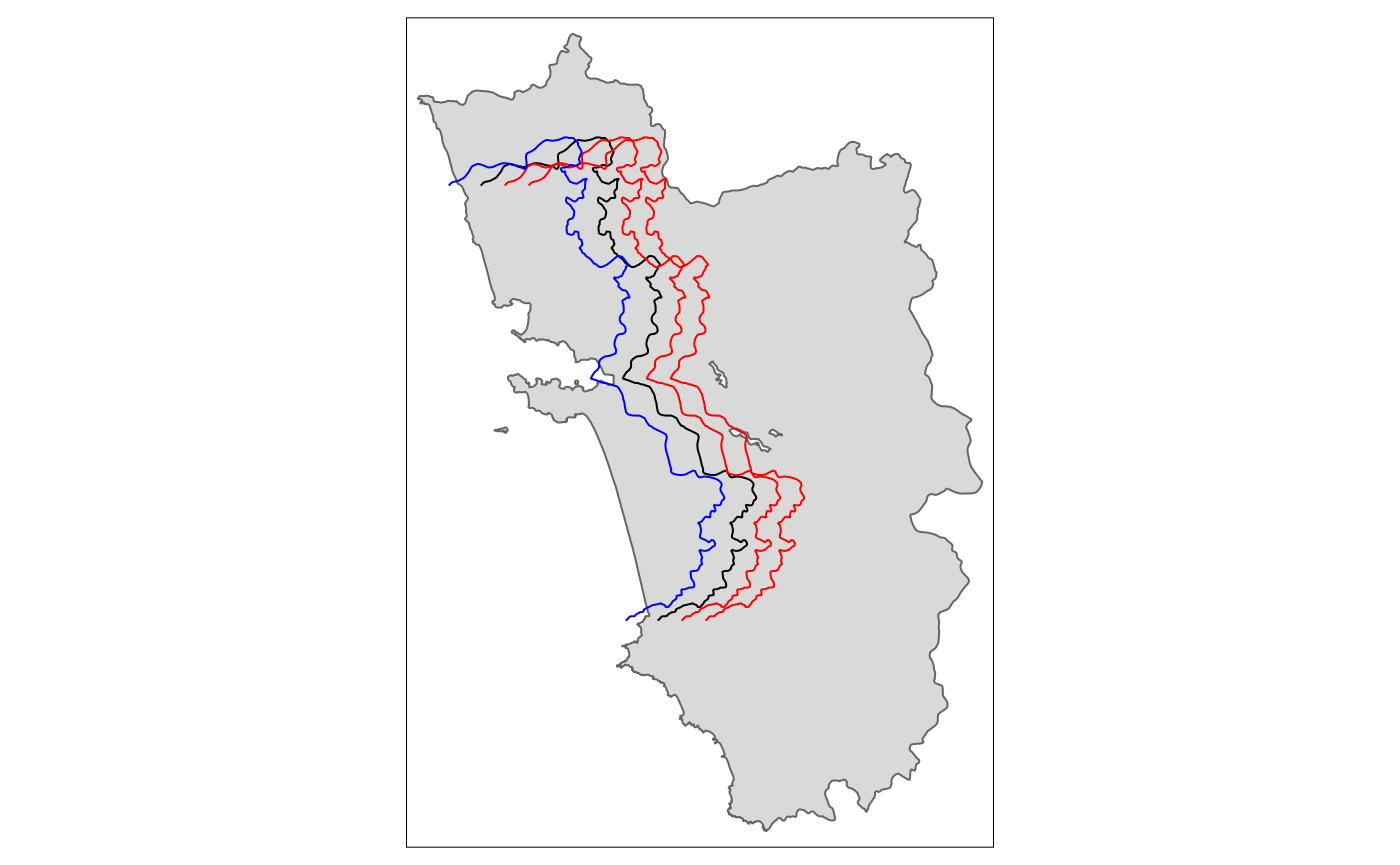

Shift

tm_shift.sf3 <- shift_border(border = cut_off, operation = "shift", shift = c(3000, 0))

tm_shift.sf6 <- shift_border(border = cut_off, operation = "shift", shift = c(6000, 0))

tm_shift.sf_4 <- shift_border(border = cut_off, operation = "shift", shift = c(-4000, 0))

tm_shape(polygon_full) + tm_polygons() + tm_shape(cut_off) + tm_lines() +

tm_shape(tm_shift.sf3) + tm_lines(col = "red") +

tm_shape(tm_shift.sf6) + tm_lines(col = "red") +

tm_shape(tm_shift.sf_4) + tm_lines(col = "blue")

tm_shift.sf_42 <- shift_border(border = cut_off, operation = "shift", shift = c(-4000, -2000))

tm_shift.sf_44 <- shift_border(border = cut_off, operation = "shift", shift = c(-4000, -4000))

tm_shape(polygon_full) + tm_polygons() + tm_shape(cut_off) + tm_lines() +

tm_shape(tm_shift.sf_42) + tm_lines(col = "red") +

tm_shape(tm_shift.sf_44) + tm_lines(col = "red") +

tm_shape(tm_shift.sf_4) + tm_lines(col = "blue")

From the last shifted line, we can already see that a movement along the x-axis quite often requires also a correction on the y-axis for the cut-off movement to be meaningful. This will be explored in the following section, together with all the other operations.

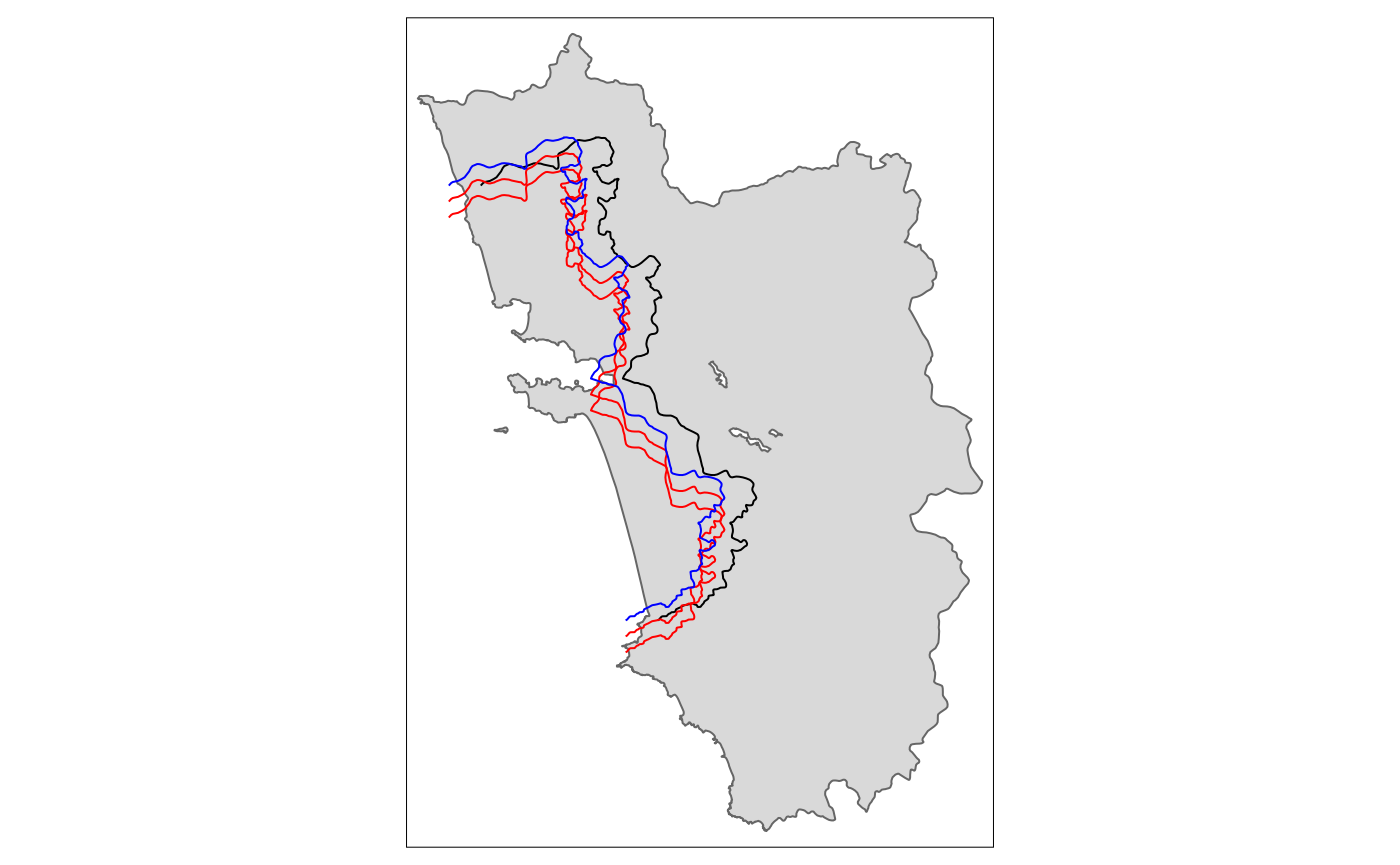

Full fledged “placebo bordering”

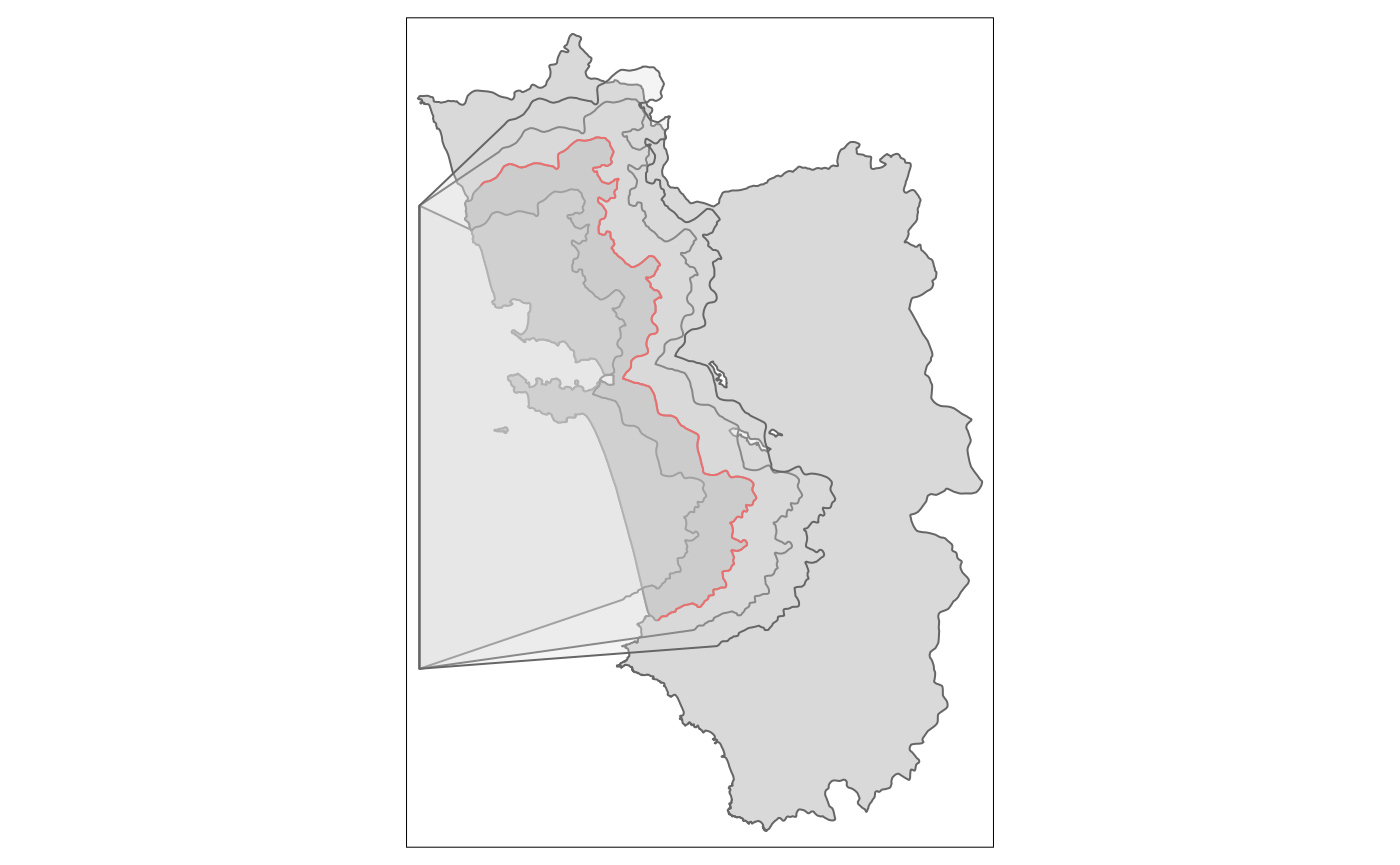

A proper placebo border ideally involves both a shift and a re-scaling for it to be meaningful.

tm_placebo.sf1 <- shift_border(border = cut_off, operation = c("shift", "scale"), shift = c(-5000, -3000), scale = .85)

tm_placebo.sf2 <- shift_border(border = cut_off, operation = c("shift", "scale"), shift = c(4000, 2000), scale = 1.1)

tm_placebo.sf3 <- shift_border(border = cut_off, operation = c("shift", "scale"), shift = c(6000, 3000), scale = 1.2)

tm_shape(polygon_full) + tm_polygons() + tm_shape(cut_off) + tm_lines() +

tm_shape(tm_placebo.sf1) + tm_lines(col = "red") +

tm_shape(tm_placebo.sf2) + tm_lines(col = "red") +

tm_shape(tm_placebo.sf3) + tm_lines(col = "red")

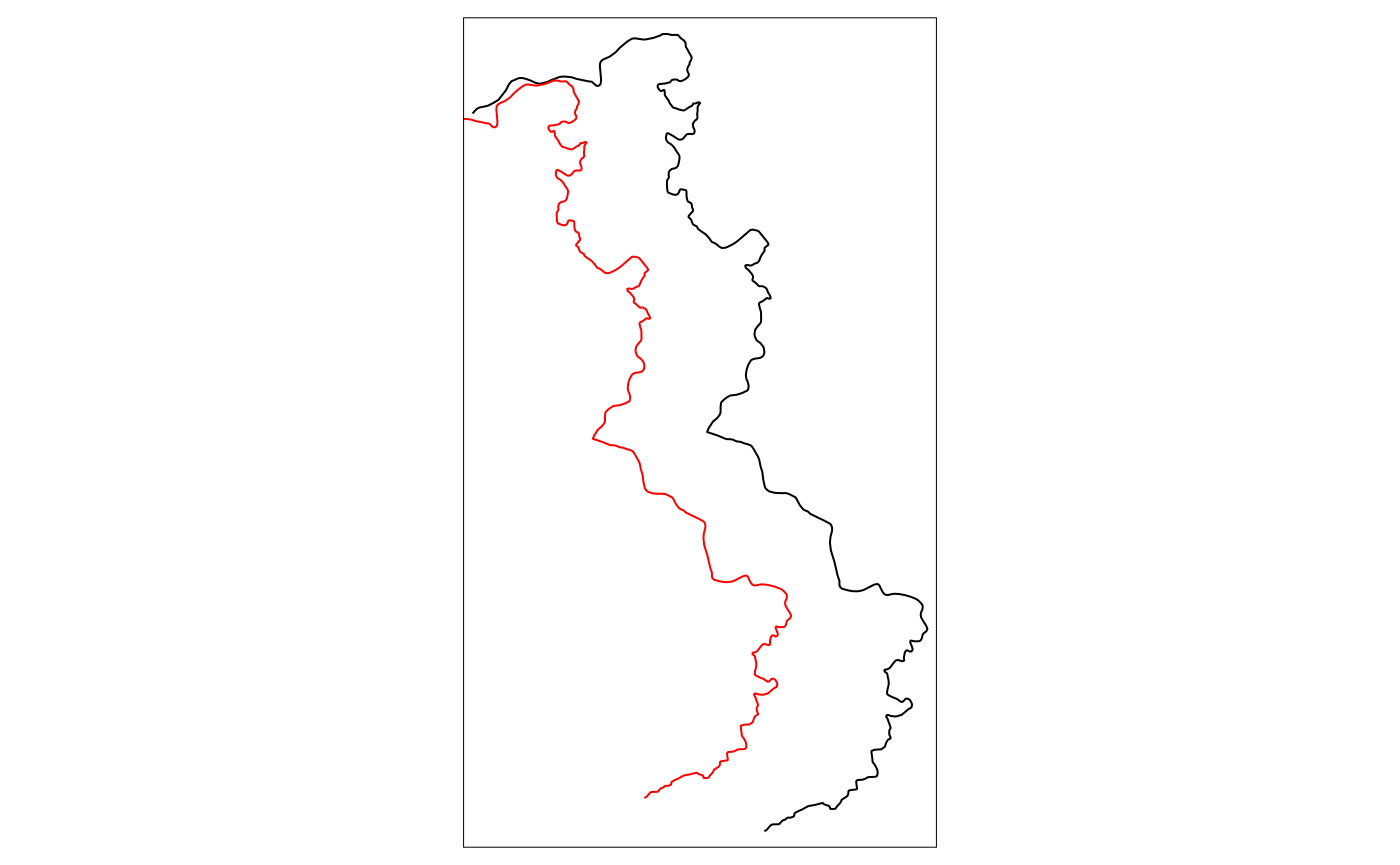

tm_shift.sf <- shift_border(border = cut_off, operation = c("shift", "rotate", "scale"),

shift = c(-10000, -1000), angle = 0, scale = .9)

tm_shape(cut_off) + tm_lines() + tm_shape(tm_shift.sf) + tm_lines(col = "red")

And the according polygons to assign the treated dummies:

polygon1 <- cutoff2polygon(data = points_samp.sf, cutoff = tm_placebo.sf1, orientation = c("west", "west"), endpoints = c(.8, .2) # corners = 0,

# crs = 32643

)

polygon2 <- cutoff2polygon(data = points_samp.sf, cutoff = tm_placebo.sf2, orientation = c("west", "west"), endpoints = c(.8, .2) # corners = 0,

# crs = 32643

)

polygon3 <- cutoff2polygon(data = points_samp.sf, cutoff = tm_placebo.sf3, orientation = c("west", "west"), endpoints = c(.8, .2) # corners = 0,

# crs = 32643

)

tm_shape(polygon_full) + tm_polygons() +

tm_shape(polygon_treated) + tm_polygons(col = "grey") +

tm_shape(cut_off) + tm_lines(col = "red") +

tm_shape(polygon1) + tm_polygons(alpha = .3) +

tm_shape(polygon2) + tm_polygons(alpha = .3) +

tm_shape(polygon3) + tm_polygons(alpha = .3)

Even though it is not as straightforward as it sounds because shifting a cutoff by a certain distance up or down and left or right is not quite enough. This is because most of the time borders are not straight lines. Thus we typically also need a shrinkage or enlargement and quite often also a transformation to change the “angle”.↩︎